Anâraptâ — listen to me

This highly unique pilot project was by far one of the most life transformational journeys that I’ve ever embarked upon.

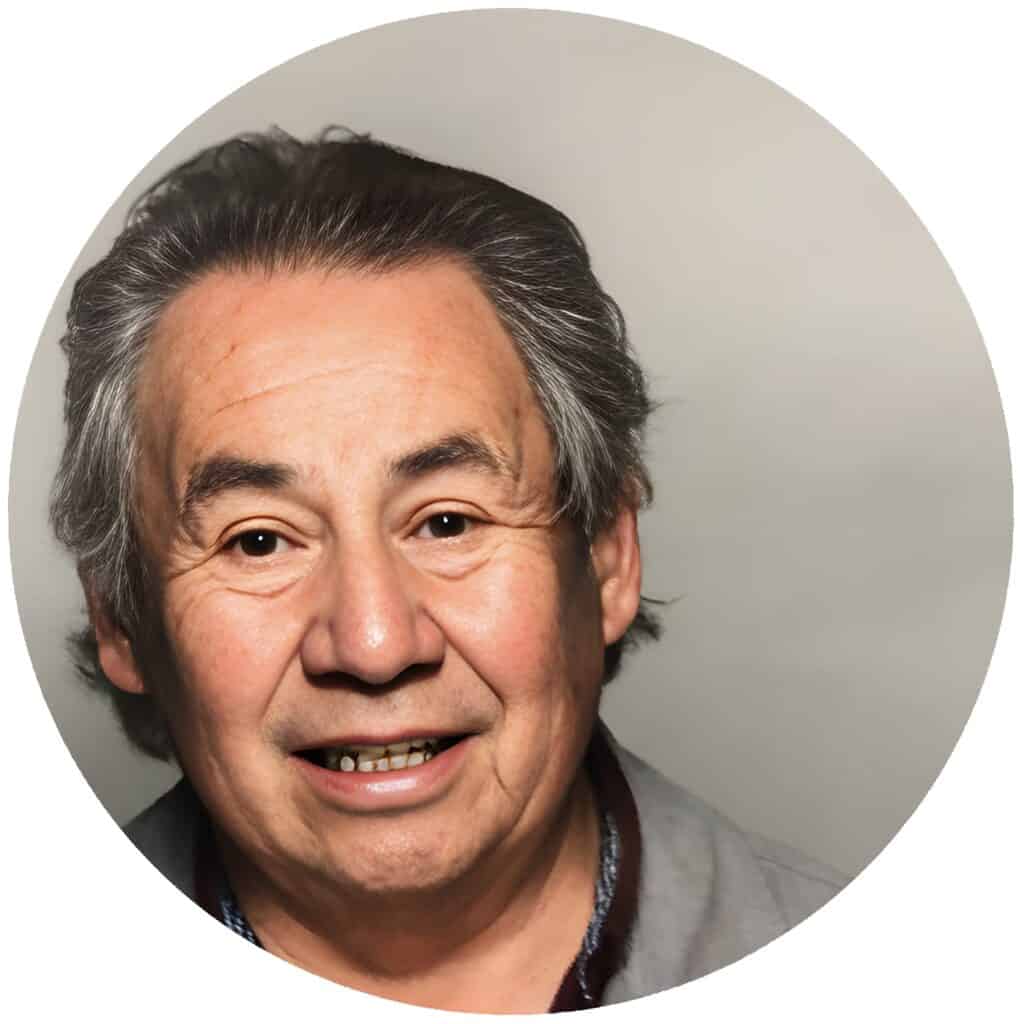

Hosted by the Banff Centre of the Arts, it was a multimedia collaboration between myself and Elder Lloyd “Buddy” Wesley. Buddy was musician and tribal historian of the Stoney Nakoda Nation.

Over one intensely productive month, Buddy and I explored our vastly different life experiences with care and love. We did so through a process of deep, active listening, which resulted in the unfolding of a profoundly beautiful fellowship in shared creativity.

CONVERSATIONS WITH DAWN

This project emerged from another very special relationship. Dawn Saunders-Dahl is an artist / arts administrator, and fellow graduate of ACAD (1996). For a number of years we were deeply embedded in an important series of conversations and regional public art activations in Alberta.

Dawn and I worked under the mantle of an unconventional artist collective called “We Need a Better Name”. Our process was fuelled by an ongoing series of bi-cultural conversations and projects concerning reconciliation. These efforts intentionally occupied the uncomfortable space between different cultures, resulting in a radical recentring of our personal notions of identity.

Ancient trade routes

Working closely together for years, it was our design to fundamentally re-establish the ancient multicultural trade routes that ran deep through this region for millennium, following the pebbled shores of the turquoise blue Bow River as it winds itself through snow capped peaks of the Rocky Mountains.

Through the transformative power of public art, we strove to confront the deeply internalized stereotypes and prejudice that each one of us — floating along currents of Canadian mainstream opinion — must face, if we honestly desire to make things go right in conversation with direct neighbors we know next to nothing about.

Much work to do

While much work remains at the national level, entrusting this task solely to the government makes no sense. Doing so is a massive assumption of trust, which risks perpetuating a cycle of fluctuating public opinion synchronized with bizarre election cycles and media sensationalism. This often leads to inadequate ‘band-aid’ solutions to the ongoing loss, pain, and suffering of First Nation Peoples.

Today, these small and often isolated communities continue to live with severe consequences. They have narrowly escaped a cultural genocide at the hands of the Canadian government. These peoples represent a nearly extinct yet priceless cultural heritage that is intrinsically bound in a sacred connection to the land itself.

Big questions

Dawn often tells people unfamiliar or uncomfortable with reconciliation that it’s about being willing to make a friend for life. The process reminds us that a true name is earned. This is true with Indigenous peoples worldwide, whose names universally speak of “us,” not “me.”

It is time we begin to make this right. Bring whatever name, tool, and skill you have to the table.

Ask big questions.

Who we are, how did we get here? Where we would like to go, and what we must do? This is an important process of inquiry, if for no other reason than it being the right thing to do.

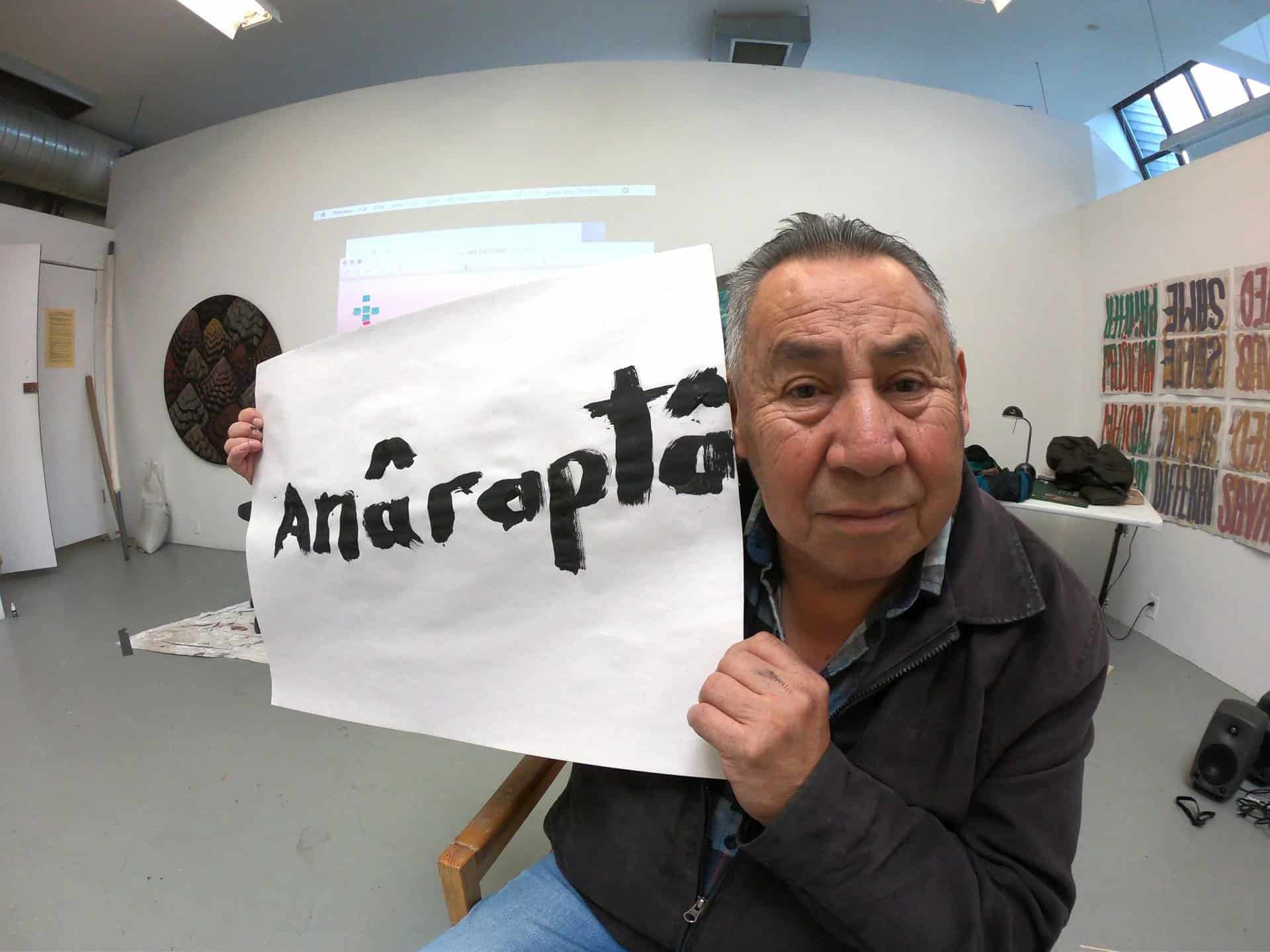

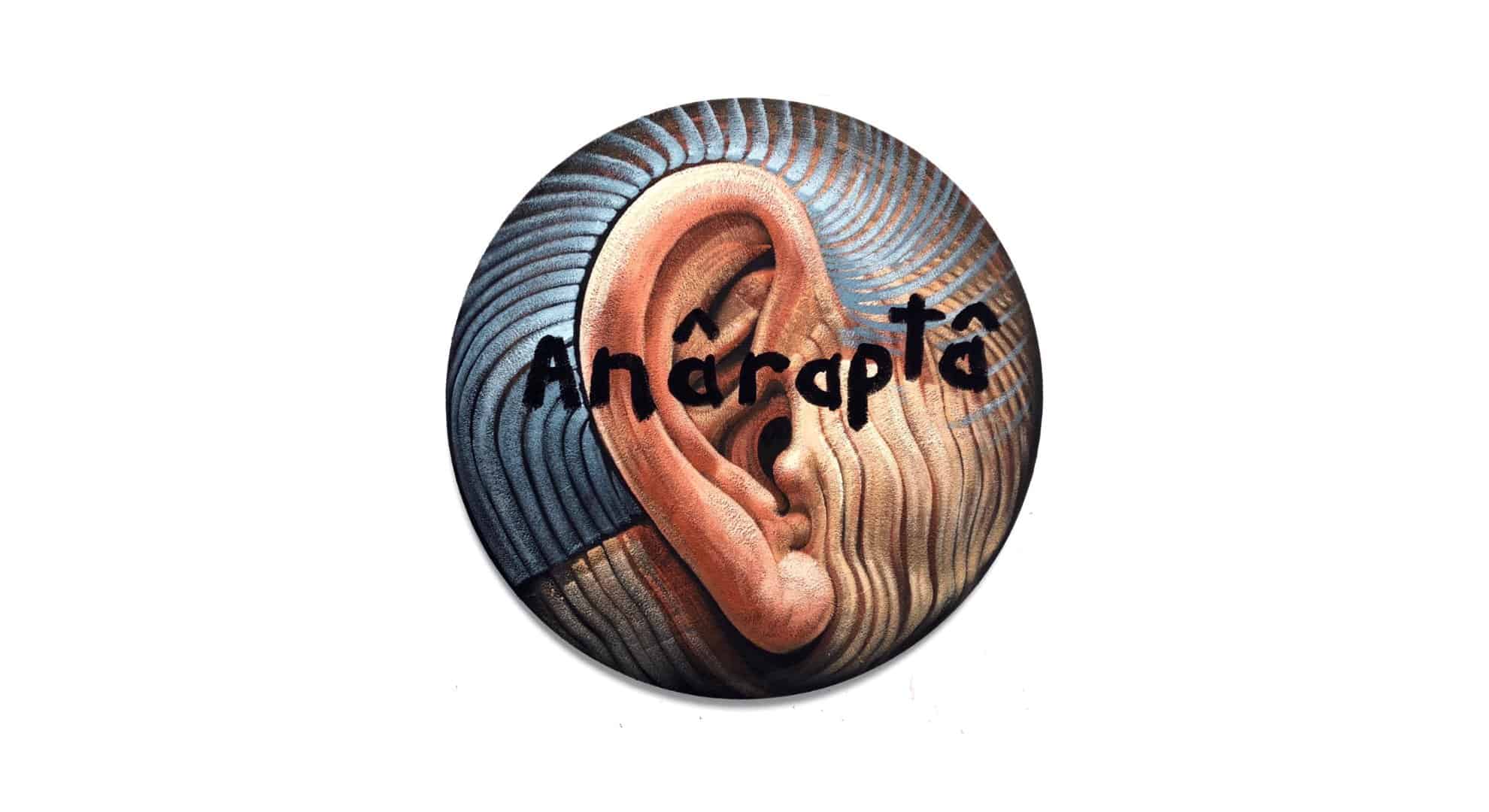

“Anarapta — Listen to Me”

This is Buddy’s ear. I painted freely, and he added a word, instantly changing the meaning of each piece in the series. Anâraptâ is an intimate ask, from one to another, to listen carefully. Buddy often withheld the meaning of the words until after the act of committing it to canvas, challenging us to play and trust.

“Iyebi — Them”

Oh, Canada.

Flags swell the patriotic heart, but not all feel that way. Buddy claimed space in this painting by adding a single word that radically shifts mean.

The finished piece was installed on the back wall of a long, narrow studio space at the Banff Centre. During the opening event held in honour of this body of work, many tables had been filled with food and drink, arranged in a shotgun formation perpendicular to this image.

Preventing views from drawing too close to the work, a line of barbed wire, which Buddy and I cut from the original reserve line on his land in Morley, blocked the way.

A pretty picture, but perhaps not for all.

“Wathûgitabi — Preparing for the Harvest”

Here’s an abstracted version of a pinecone I found while wandering round the region. One of a million.

Its meaning is related to the wisdom of the squirrel as she collects her harvest for the long winter.

Now more than ever, it’s crucial to recognize, listen to, and incorporate teachings from the First People, especially in a time of tremendous environmental and political instability.

“Wanîch — Saved”

What does it mean to be ‘saved’?

Canadian residential schools erased the given names of hundreds of thousands of First Nation peoples in this country, not long ago. It was a systematic attempt to erase their culture by imposing Eurocentric naming and identity norms, often in the name of Christianity.

Today, small and often isolated communities continue to live with the severe consequences of loss of culture, trauma, and pain.

If anyone out there wants to have conversations about the Indian Act, or about our contracts with the corporate state of Canada in general, I’m always game.

“Châkathnude — Cord of Life”

The cord of life runs through each link of the spinal column. Here’s a segment where the river once ran. Dried and bleached, it is now devoid of the tissue that once anchored it to life.

Like many on the journey of reconciliation, I believe it’s time to invest ourselves in learning from First Nation communities.

By actively taking control of our communities, in an open-sourced, decentralized manner , we can confront the global corporate destruction upon us daily.

It is on us to breathe new life into old bones, instead of begging for change from governments who continually railroad trails of broken promise to the people toward big business conflicts of interest.

“Wakâsatâga — Matriarch”

Our names, gifted by parents and society, give word to the world about who we are. Our self-esteem heavily depends on our feelings about our name. When we dislike our label, it’s difficult to feel good about ourselves.

This is a portrait of a local Stoney Nakoda Elder. With a knowing wink and a pause to her softly spoken stories, her eyes lock with yours. They tell mothers’ tales of melancholy, maturing wisdom, and magic. Her eyes are a perfect mirror to the depths of her wisdom and life experience. Her face, endlessly animated and kind featured, dances in step to every emotional beat of her heart’s drum.

I don’t know for certain if she liked this painting or not. She did however hit me in the leg with her cane when she saw the work.

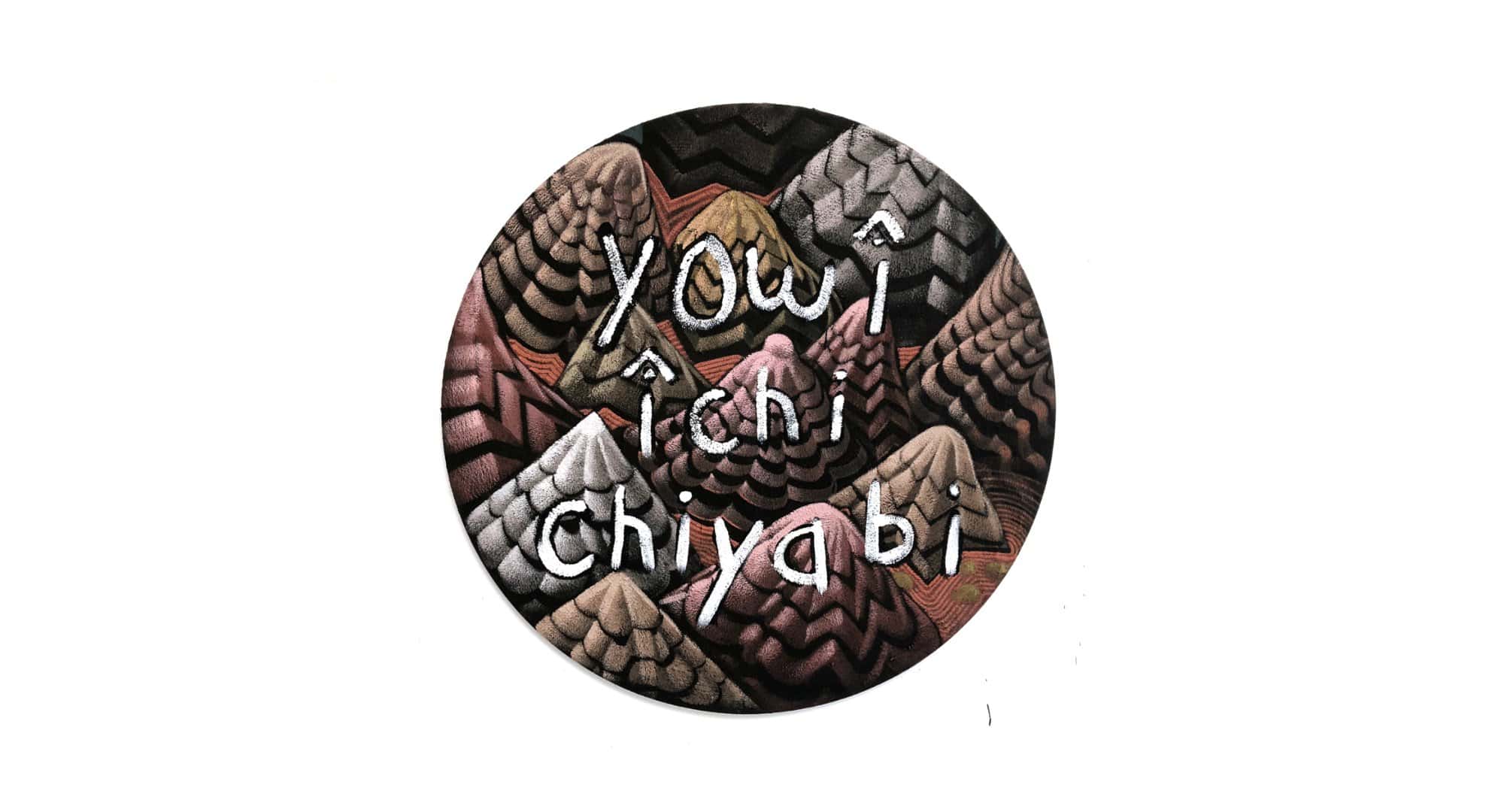

“Yowî îchi chiyabi — These Mountains”

Indigenous identity directly connects to nature itself. Therefore, any attempt to answer the call of reconciliation must include immediate action to protect the environment.

This requires strong community co-management of shared resources and the fair redistribution of power. Decentralization is key.

As we reclaim and assert our identities against a history of dispossession and erasure, we must consider the moral and ethical obligations that accompany this recognition.

”Apiîchiyabi — A Work in Progress”

This one says it all. Aren’t we all, and to some degree, isn’t everything in life a bit like that? This painting certainly is a work in progress, and yet now it is done.

The video below features a Timelapse video taken of Buddy’s place in Morely, AB.

It opens with a prayer, and includes various layered sounds recorded during our collaboration, both on the reservation and at the Banff Centre.